Godly Monopoly and the Philosophy of Peter Thiel

On Rene Girard, mimetic desire, Zero to One, and brief introduction into the complex philosophy of Peter Thiel

From handpicking then Vice Presidential candidate JD Vance, building surveillance software to investing in biotech companies promising to defeat death itself, Peter Thiel might be the most fascinating—and terrifying1—man in tech. His influence reaches nearly every facet of modern society, yet most people outside tech bubbles have never even heard his name.

I've been both fascinated and frightened by Peter Thiel since 2020. After spending five years closely following his projects, it's become sickeningly clear that Thiel has a precise vision of what the world should look like—and he's been methodically building toward that vision for decades.

This is part one of a three-part series where I'll break down Thiel's philosophy and far-reaching impact, starting where he's known best—as a tech founder and author of Zero to One, the de facto Silicon Valley startup handbook that has influenced a generation of entrepreneurs. But as we'll see, his ambitions extend far beyond building companies.

PayPal Guy

Unlike many modern tech founders whose names are synonymous with cartoonishly nerdy billionaires—your Musks, Zuckerbergs, and Bezos of the the world, who effectively became the faces of big tech—Thiel has accomplished similarly transformative feats while remaining deliberately obscure. Positioning himself as Silicon Valley's quiet kingmaker, discreetly crowning kings from tech to politics and sending his acolytes out to craft the culture in his image.

After studying philosophy and law at Stanford, he worked as a derivatives trader at Credit Suisse before co-founding PayPal in 1999 amid the dot-com boom, making him part of the notorious "PayPal Mafia"—a distinctly geeky billionaire boys club who would go on to craft the culture of modern Silicon Valley and big tech.

With a net worth of around $21 billion (his PayPal co-founder Musk has a net worth of $410 billion), Thiel has invested in over 100 companies, runs multiple investment funds focused on backing "promising" young founders with "contrarian" ideas, and has quietly extended his influence deep into the American political machine without the pomp and circumstance typically associated with equally powerful cultural figureheads.

Thiel, Rene Girard, and Mimetic Theory

Thiel’s worldview is heavily informed by philosopher and anthropologist René Girard2, whose lecture Thiel attended as a Stanford student. Girard's core work, mimetic theory, or rather Thiel's interpretation of it, would serve as the foundational belief informing everything he would go on to do, from his startups, investments to his book, and even painfully referenced during a three-hour Joe Rogan podcast3.

A Brief Primer on Mimetic Theory

In mimetic theory, mimesis refers to human desire, which Girard believed was not innate but learned through imitation.

"Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires."

- Rene Girard

The Desire: Humans do not innately know what we want; we learn what to want by observing others. It's watching someone's perfectly curated life on an Instagram story and suddenly feeling the desire to go to Spain and get skinnier: the twist of inadequacy at your own previously fine existence.

The Rival: If I want what you have because you have it, then you become both my model and my rival. Whether it's a coveted job, wealth, or even a romantic conquest—our desires are finite in capacity, and our role models, the ones we modeled our desires after, quickly become our competitors.

The Scapegoat: From holy wars to social media subtweeting, violence ensues when rivalry and desires escalate. Girard argues that societies solve this by unconsciously picking one person or group to blame for all problems, a scapegoat to absorb all the collective tension anything from another nation-state or political opponent.

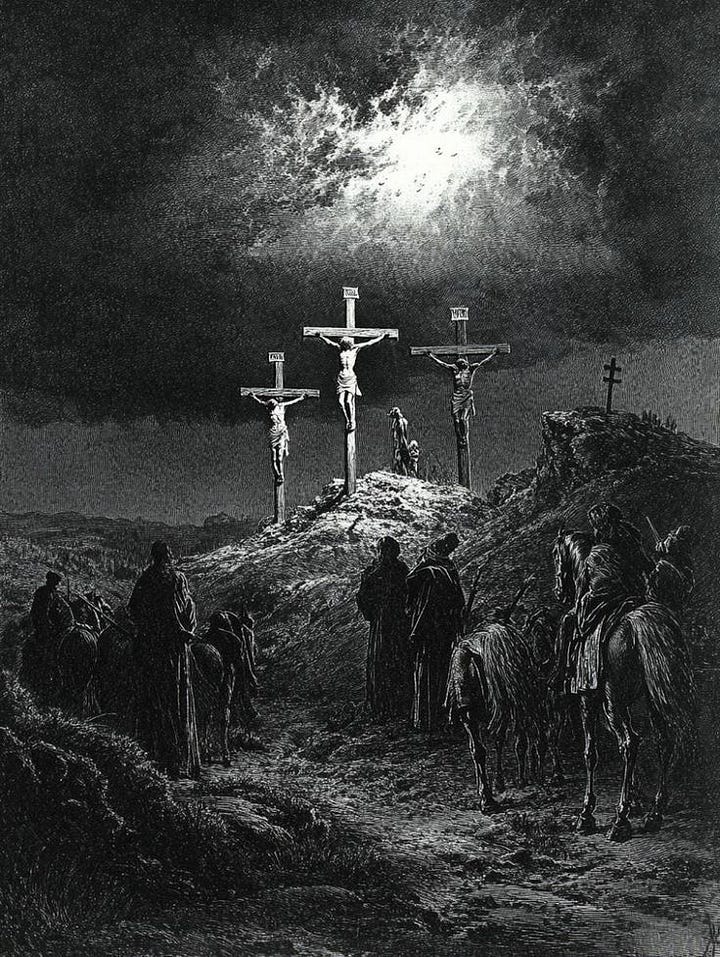

Jesus Christ, The Mimetic Martyr

Girard and Thiel see Christianity as humanity's most significant breakthrough as it grants us freedom from this periodic violence through the sacrifices of Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ was the ultimate martyr, crucified for all of humanity's sins, essentially absorbing the evils caused by our mimetic desires. He taught us to love our enemies and forgive, relieving us from our predestined heathenism.

Thiel, a Christian, interpreted Christ's gospel in a decidedly elitist manner. If Christ, the chosen son, could transcend mimetic violence and bring order to the world4, perhaps specific exceptional individuals, like Thiel and his chosen few could, too

What is the basis of imitating Jesus? It cannot be his ways of being or his personal habits: imitation is never about that in the Gospels. Neither does Jesus propose an ascetic rule of life in the sense of Thomas a Kempis and his celebrated Imitation of Christ, as admirable as that work may be. What Jesus invites us to imitate is his own desire, the spirit that directs him toward the goal on which his intention is fixed: to resemble God the Father as much as possible.

― René Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning

Zero to One

Thiel's messianic vision of the future comes complete with its holy text. In 2014, after successfully exiting PayPal, Peter Thiel wrote Zero to One5, which would become the de facto bible for aspiring Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. Thiel doesn't explicitly mention mimetic theory, Girard, or scapegoats in the book(after all, he's writing for tech bros who aren't too fond of reading), but the text is a not-so-subtle translation of mimetic theory veiled in business advice.

The central thesis of Zero to One is simple: to build a successful company, one must reject competition and seek a monopoly instead. Find a niche, capture that market, and scale from there. On first read, it sounds like the Silicon Valley version of the monocled Monopoly man whispering trade secrets directly into the ears of the chosen few ambitious enough to pick up a book and read it.

The best entrepreneurs know this: every great business is built around a secret that’s hidden from the outside. A great company is a conspiracy to change the world; when you share your secret, the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.

Peter Thiel, Zero to One

While rejecting competition initially sounds anti-capitalist, it's actually consistent with how most successful companies originated. Amazon, Meta, and Apple didn't become titans of their respective industries by frantically developing feature after feature quicker than their rivals; they built products so distinct they could skip the competition entirely.

The book also emphasizes proprietary technology and secrets—the edge a company gets by maintaining "stealth mode" and keeping their research locked down, as opposed to the open-source, collaborative framework. A recent application of this philosophy is OpenAI's recent pivot from open research to closed models, which has allowed them to become the AI company.

By building monopolies and dominating markets, entrepreneurs can supposedly escape mimetic rivalry entirely. Instead of competing with others for the same limited resources, they create entirely new categories where competition doesn't exist. The goal is to dominate in a way that allows one to transcend the bounds of predetermined possibility.

I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible - Peter Thiel

Thiel’s Chosen Ones

Beyond his entrepreneurial ventures, Thiel is a prolific investor and philanthropist, funding promising ideas and young people. Through these investments, Thiel gets to live out his christ-like vision in two key ways:

By investing in ideas he deems important, Thiel wields enormous influence over the future, deciding which companies get funded and which don't, from defense, infrastructure, to biotech. Thiel uses his immense capital to back the companies and technologies that align with this worldview. (Also why he has signifcantly less billions than his peers)

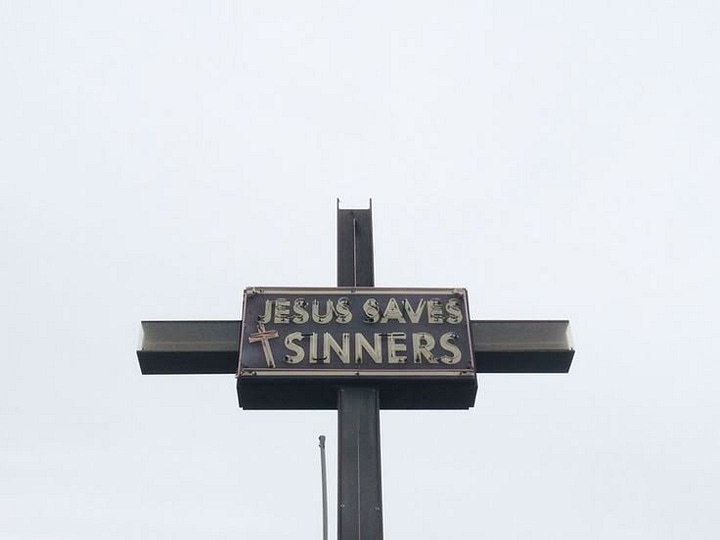

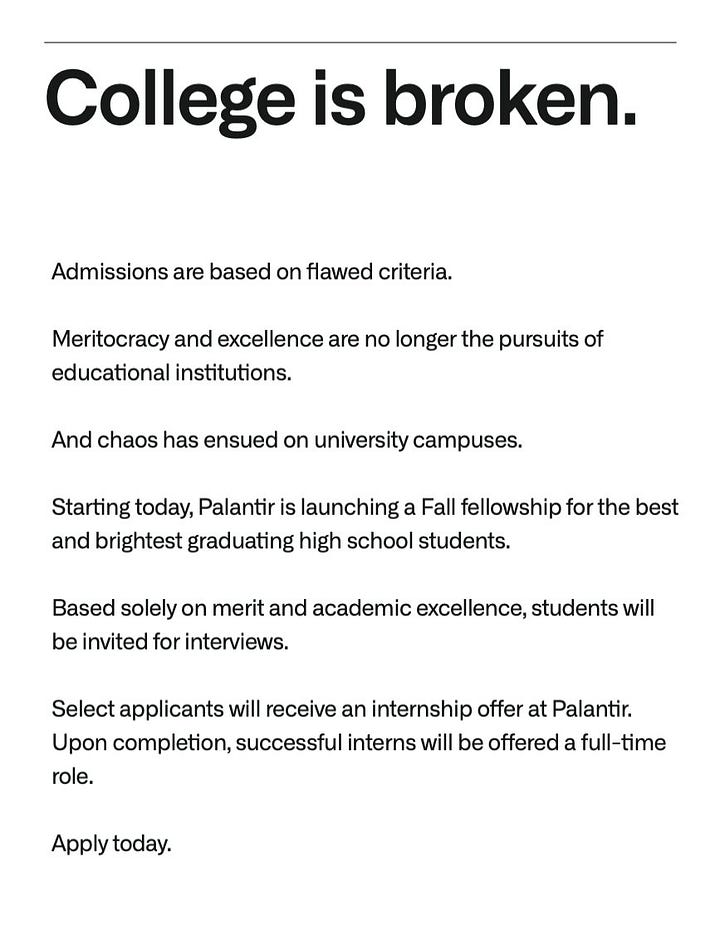

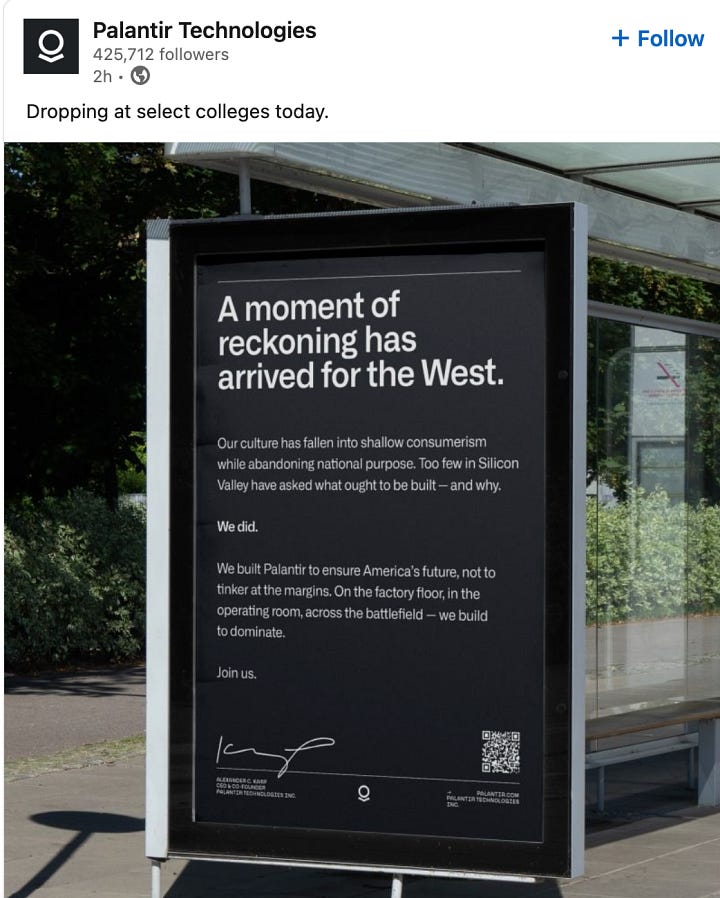

Through programs like the Thiel Fellowship, Founders Fund, and the Palantir Fellowship, he can identify and cultivate what he sees as the next generation of exceptional founders to carry on his chosen legacy.

The Thiel Fellowship6 gives $200,000 to promising young founders to drop out of college and pursue their ventures. The Palantir Fellowship7 targets high school students to forgo the "indoctrination" of university and get what they call the "Palantir degree"(the irony is unfortunate). Founders Fund invests in companies that align with his contrarian vision. All of these programs are highly exclusive, with acceptance rates below 0.1%, making them among the most coveted opportunities in tech. Getting accepted is akin to being anointed by Thiel himself—a Silicon Valley christening that marks you as one of the chosen, opening doors to elite networks, funding, and the outsized capability to influence the future of tech.

While many of the companies, ideas, and people Thiel backs are genuinely talented and are building wonderful products, the contradictions in his approach are striking. A large part of the marketing for programs like the Thiel Fellowship revolves around encouraging students to reject the "trap" of university and instead go out into the real world to "build" and make "meaningful" contributions to society. Despite holding two degrees from Stanford, Thiel himself regularly disparages colleges, once likening elite universities to "Studio 54 nightclubs" that are unjustifiably exclusive and "once you get in, not worth the hype."

Yet for someone who allegedly opposes the validity of these traditionally elite institutions, Thiel isn't scouring trailer parks in the Great Plains searching for hidden-gem geniuses—the promising futures he's cultivating are born, bred, and cosigned by the same elite backgrounds he claims to reject.

This reveals the fundamental contradiction: through his programs and the culture he played a pivotal role in developing, Thiel has created his own version of the elite institutions he publicly scorns, complete with exclusivity, prestige, and gatekeeping, one where he gets to decide who gets in and what is taught. Allowing him to dodge the the messy compromises of modern society, which he believes to be "woke" and stifling of innovation and societal progress.

It's a godly monopoly that allows its adherents to embody the self-serving sensibilities of Gilded Age robber barons while enjoying the spiritual self-indulgence of believing only they know how to save humanity. This system perfectly serves Thiel's vision: he positions himself as both anti-establishment trailblazer and aristocratic kingmaker, rejecting traditional power structures while building new ones with himself not at the center, but floating above the entire structure as its architect and deity.

The Valley of Thiel

Many still mistakenly still associate Silicon Valley's culture with the hippie counterculture movement of the 1960s, when the San Francisco Bay Area was an epicenter of social and technological progress built in opposition to the status quo—anti-war, anti-government, and anti-establishment. The counterculture movement of the '60s gave rise to startup culture as we understand it today, with students from Berkeley and Stanford rejecting the stifled approach of East Coast professionalism to build progressive innovation in the Bay. But long gone are the days of peace, love, and rock and roll. While Silicon Valley remains a center for innovation, it no longer represents a rejection of legacy systems—it has created a new legacy of its own, one that's far removed from its counterculture roots.

Technology as we know it is no longer wackjob fringe ideas built by long-haired hippies in California—it's the essential infrastructure that the world is built on. While it may have once been radical to forgo that investment banking job on Wall Street to work at a hot new startup in Palo Alto, that's no longer the case.

Yet the culture still clings to its contrarian self-image. While some companies genuinely make bets that nobody else is making, modern startup culture is teaming with Thiel's acolytes, armed with knowledge from Zero to One and Paul Graham essays—bright, ambitious young people who seek to be contrarians themselves, aspiring to build the next zero-to-one company, searching far and wide for counterintuitive insights to create the future.

The evidence is nowhere more visible than on Twitter/X8, where the tech startup community congregates to share their insights. Whether it's company that is building the "undetectable AI assistant that allows you to cheat on everything," that has gained millions of impressions over the past several months for its distribution-first approach to building companies or the countless other products claiming to be "the last [insert thing] you'll ever need" or promising to "revolutionize [industry]," the culture at large—especially young people attracted to the idea of being a "founder"—over-indexes on Thiel's view of monopolizing a market and being a contrarian.

“If you’re less sensitive to social cues, you’re less likely to do the same things as everyone else around you.” - Peter Thiel, Zero to One

The pursuit of contrarian thinking has become so universal that it might be contrarian to just be normal and do normal things. What used to be genuinely rebellious—dropping out of college, rejecting big tech jobs to build a startup—has become the status quo in this insular bubble.

The result is a culture where everyone tries to transcend mimetic desire by mimicking the person who sought to transcend it. Young, well-meaning, talented people unknowingly embody exactly what Girard predicted: when everyone tries to escape mimesis, the attempt becomes mimetic. They're all building in the contrarian image of the man himself, not realizing that their contrarianism has become the very thing they're all imitating. After all, the world is cruel, and not everyone can be the chosen one destined to free humanity from its sins and suffering, and the messiah preaching anti-mimesis has become the most mimicked man in tech—one of the many fascinating contradiction of Thiel’s story.

You can support my writing by engaging with my work, sharing your thoughts, and reaching out. Find me on X , or buy me a coffee.

Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972.

Thiel, P., & Masters, B. (2014). Zero to one: Notes on startups, or how to build the future. Crown Business.

The things I do to gather primary sources

Fascinating

Thanks for writing this. Well researched!