Big Brother is Always Watching (instagram reels)

on the digital panopticon and my instagram reels

I love Instagram reels. I particularly love curating a unique, strange content feed to send my friends the most absurd videos. I know my sweet friends open up their Instagram DMs with me with an air of disgust you would have when your dog has dropped a dead bird at your doorstep—but your labrador retriever is tongue-out, tail-wagging, proud of its gift that it has just hunted for its owner. You can't be mad because you know your dog is a hunting dog, and that's just what they do: the dead bird is a token of love and appreciation, so you just let it all be. Similarly, my friends don't want to see whatever manufactured shock value content I'm sending them, but I am a dog with a bird in my mouth displaying affection in the only way I know how, so they tolerate it. (I'd like to think my friends appreciate the sentiment of me seeing something absurd and immediately thinking of them.)

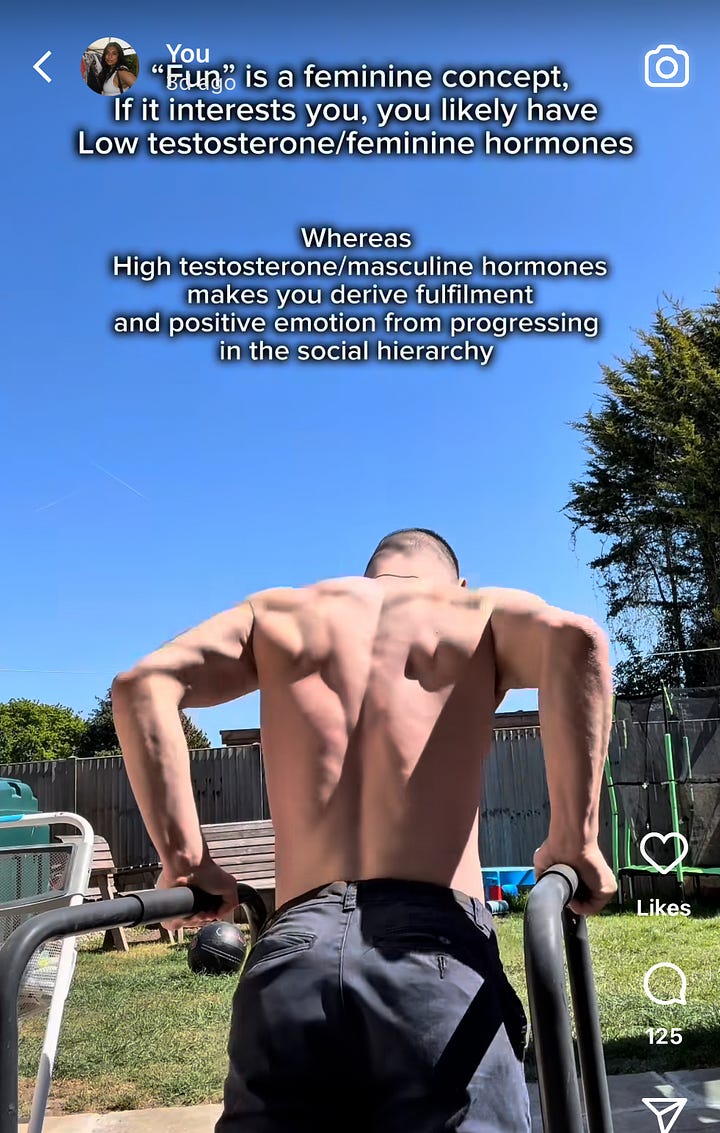

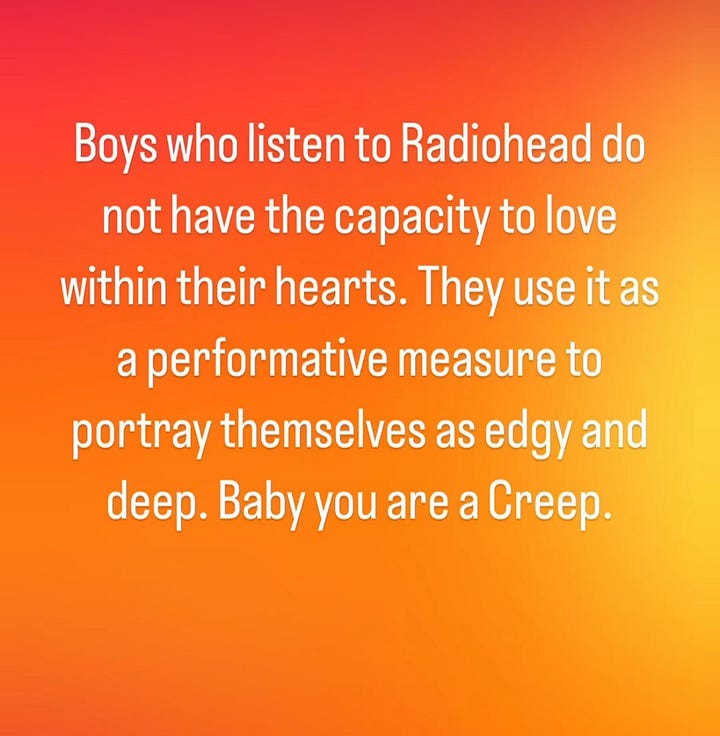

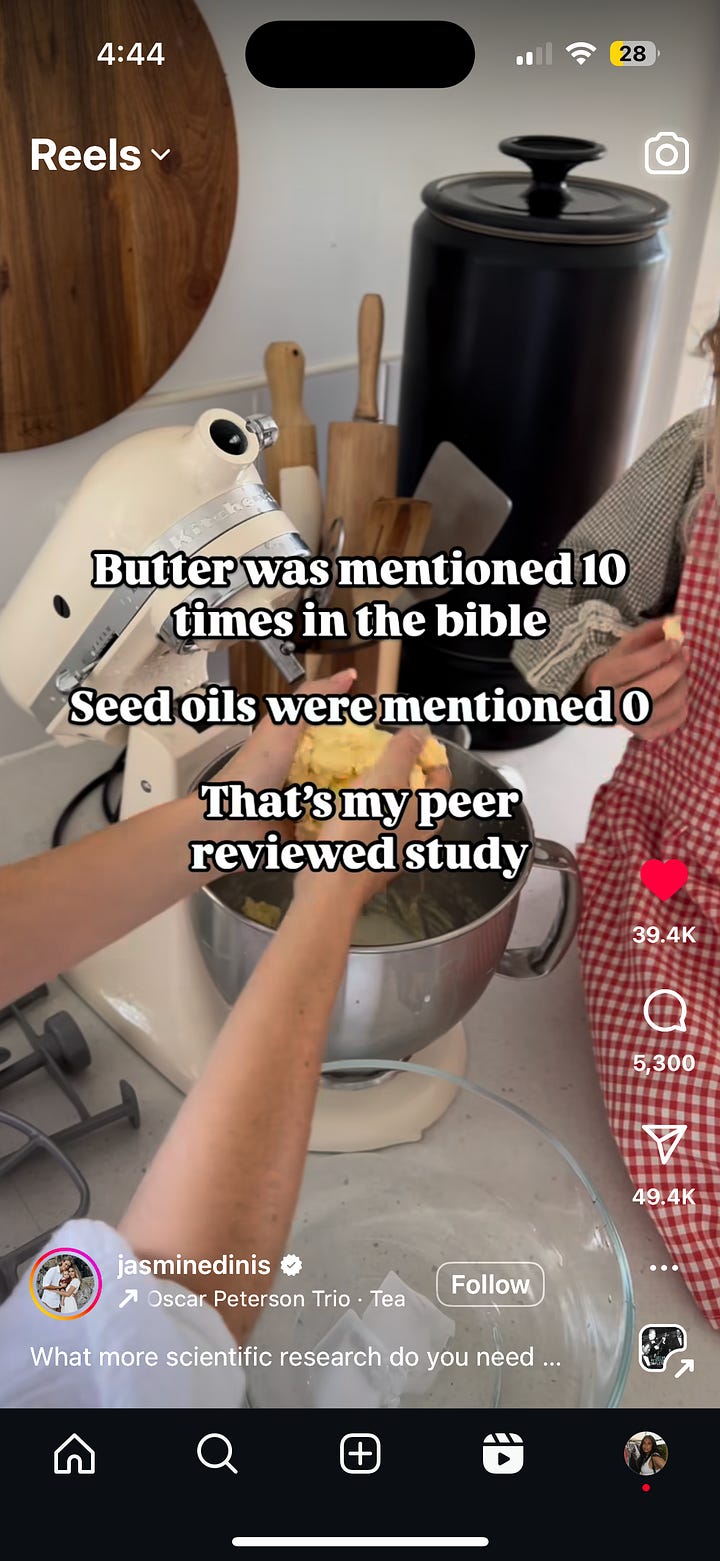

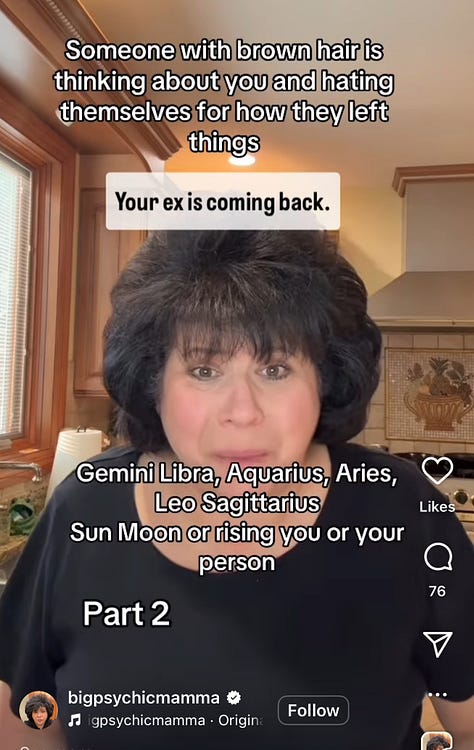

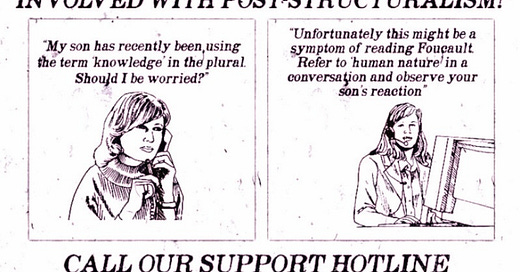

I consider myself a sort of an Indiana Jones of Instagram reels. I'm lying in bed, scrolling with a noble quest: curating a feed of videos so rich with subtext they could belong in the Library of Alexandria. Discovering content so layered with complexity that it will be offered as a primary source to analyze in an anthropology class someday. To accomplish this sacred duty of finding and distributing the internet's most absurd offerings, I have to "like" and engage with this content.

The ontology of an Instagram "like"

At its core, what is an Instagram "like"? When I double-tap an Instagram reel, what exactly am I liking?

Consider the classic evil boyfriend defense: "No babe, I just liked the nature in Hawaii. I didn't even notice she was in a bikini—you're being really insecure." While he may be a master manipulator, he's not wrong about the ambiguous nature of an Instagram "like."

A successful Instagram reel is packed to the brim with content in just one thirty-second clip. There are many interconnected components in a video: the creator, the punchline, the music, the background, and so much more. When I like a video, I have no way to indicate what particular element of the post moved me to double-tap.

Does a “like” on Instagram mean I agree with something? By liking something am I cosigning it? Endorsing it?

I, for example, have had a decade-long obsession with conservative Christian trad-wife content. Content from blonde Protestants in long dresses with many children explaining to me how to dress in a "God-honoring way." Of course, I am ideologically opposed to the messaging in these videos, and I understand that it's not an accurate representation of Christians and Christianity. But I will tap that like button until my fingers fall off whenever I see one of these videos on my feed. I press like because I am fascinated, I want to see more of them, and I want this woman to make money off her content so she can continue to feed her seven children.

But public likes mean that my friends can see what I've liked. Sometimes—oftentimes—it's questionable content, and then my friends send it back to me asking me to explain why I liked something. Then I have to explain myself.

The nebulous nature of Instagram offers no room for nuance. This is why reactionary "rage-bait" content performs exceptionally well on these platforms. When likes are public, all that nuance is left to the imagination of whoever sees that like in their feed to surmise why I liked a particular video. If only there were a button that says, "I am liking this for ironic, anthropological reasons but am fundamentally opposed to the core message of this video."

While it may appear a seemingly harmless habit, the dynamic exposes an insidious, underlying reality: I am constantly being surveilled even when I’m scrolling in the privacy of my own comfortable room. The knowledge that my likes are visible transforms my private consumption into a public performance. Instead of tapping away at anything that makes me laugh, I now hesitate, wondering who might see it and what assumptions and judgments they will make of me. Encroaching on my freedom, I am robbed of the agency even to numb my own brain.

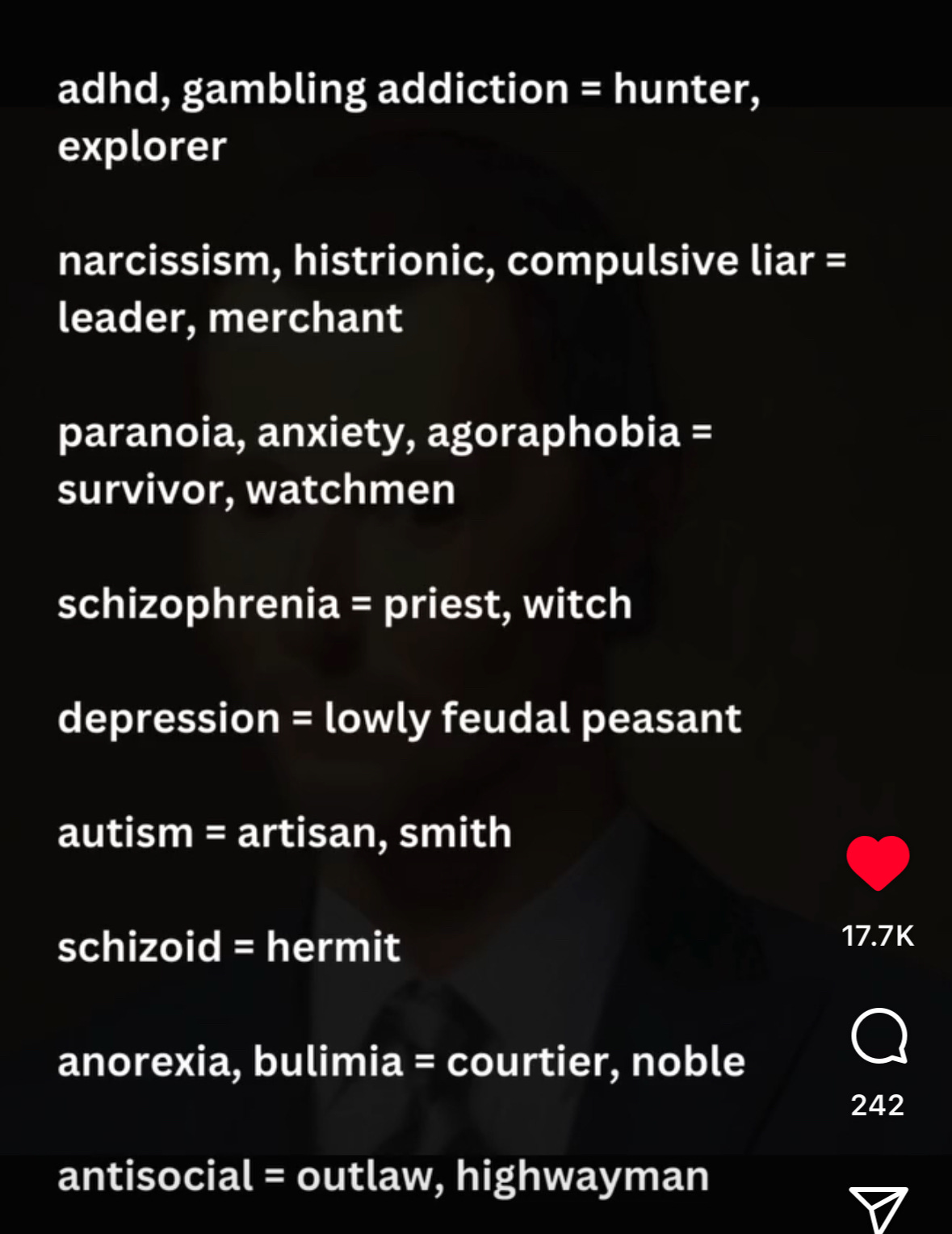

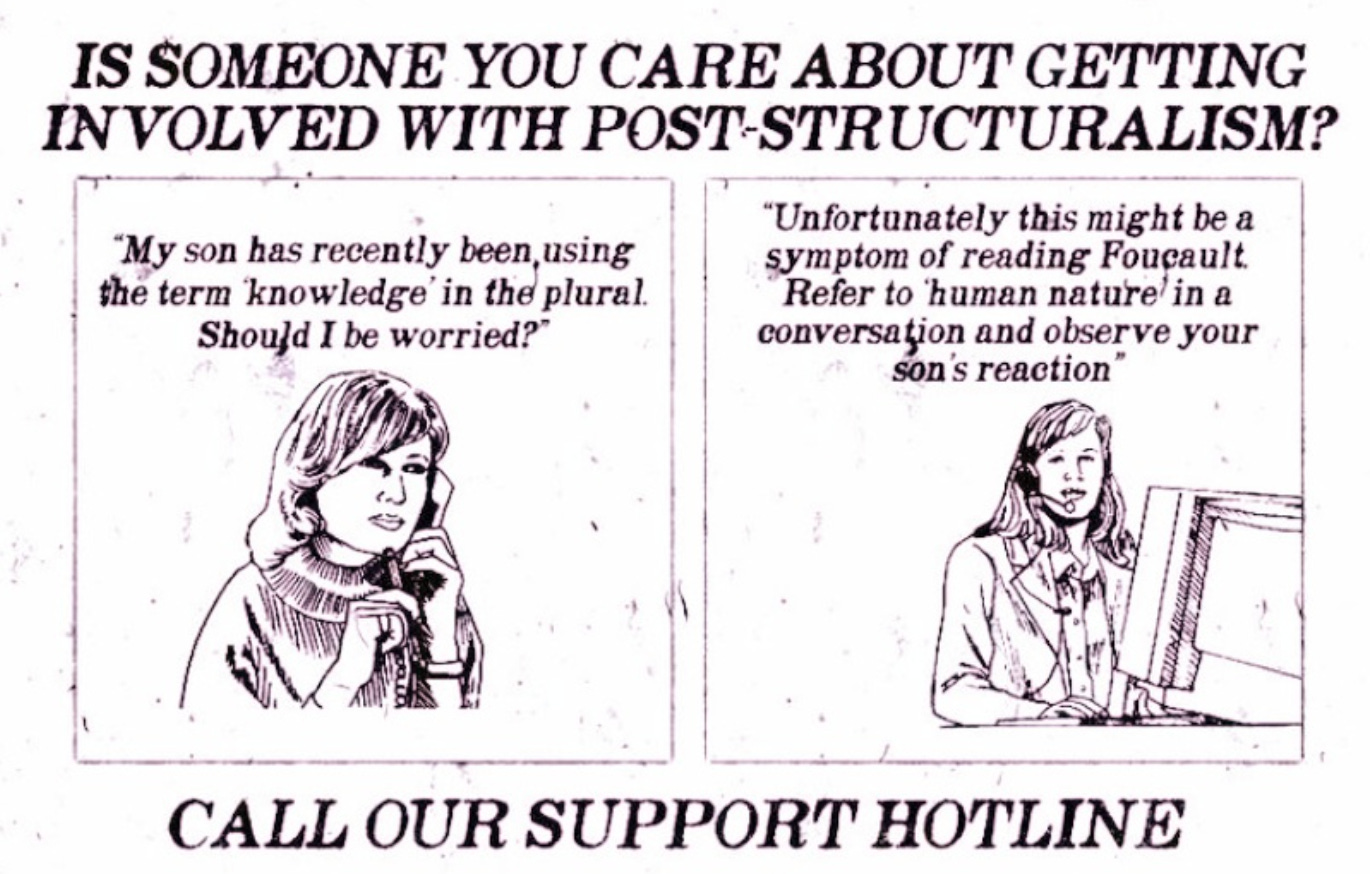

Foucault and the Panopticon

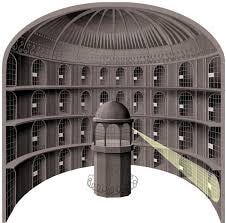

It's a sickeningly Orwellian fantasy that we can examine through the lens of Michel Foucault's concept of the Panopticon. The original idea of the Panopticon (pan = all, optic = seeing) came from philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the nineteenth century as a model for prison design. Picture a centralized watchtower in a prison that allowed one guard to potentially watch any prisoner, but not all prisoners at once.

When prisoners believe somebody could be watching them at any time, they behave as if they are being watched, resulting in better behavior through perceived surveillance. One guard can't actually monitor everyone simultaneously, but the possibility of being observed changes everyone's behavior.

In the 1970s, Michel Foucault applied the Panopticon to modern societal power, control, and surveillance issues, primarily in the context of industrial labor and social dynamics. The idea of being monitored influences individual behavior, making people comply with rules without having to enforce these rules directly. Foucault, unfortunately, died before ever getting to experience the unadulterated joy of giggling away at Instagram reels, but I am sure he would have many thoughts about the state of social media surveillance.

The public nature of Instagram likes is an ideal model for understanding the dynamics and dangers of panoptic control.

If I see a video on my feed, I can see who has liked it, which gives me interesting insights about my friends, to say the least. But it's an issue of the pot calling the kettle black. Because if some weird video shows up on my explore page, that means Instagram has identified me as someone who would enjoy "7 tips for managing life with your alcoholic husband," or "witchy love spell to get your ex back," or "ASU frat boy ferda chant."

Even though my engagement with these videos is totally ironic and satirical, I subconsciously will not like some of with these posts because I don't want to be perceived as someone who would consume this content unironically. This creates a perpetual state of self-surveillance. I don't know if, when, or which one of my friends will see my likes, but I know they can. And now I can't even scroll in peace because there's an all-seeing eye above me, watching and judging, that stops me before my finger even presses the button and keeps me scrolling along.

This idea of how the state of public surveillance creates rigid self-surveillance is the core of what Foucault explains about the Panopticon in Discipline and Punish. Your manager at work can't monitor you at all times, but they can sometimes, which means for the eight hours you are clocked in at the office, you type away at the computer like the stiff-necked worker-bee you are. The same idea applies to public surveillance. I can't throw a tantrum about egg prices in the middle of Trader Joe's because other people are there, and I don't want to embarrass myself and be perceived as an uncouth cretin lacking fundamental social graces. And nowadays, I not only have to worry about the fifty or so people grocery shopping at Trader Joe's on any given day, because all of those people have phones, and a public outburst could get me recorded and become the next viral video on Twitter. And in typical Twitter fashion, my random outburst about the price of eggs would likely be construed with reactionary subtext and I'll become "Brown woman rages at Trader Joe's—here's why we should get rid of H1B visas."

The knowledge of being surveilled, even though people are not out to get us and watching us all the time with malicious intentions, is enough to control our behavior and prevent us from liking strange videos that make us laugh.

What about my digital footprint?

I remember vividly sitting in the computer lab of my elementary school in fifth grade, getting my first talk on internet safety. This was 2014, and I was already chronically online as a ten-year-old, my internet use mostly confined to the harrowing corners of YouTube, Twitter, and Tumblr.com1. I was too young to have anything insightful to post, but I sure did lurk.

The advice my teacher gave me was to not post anything I wouldn't want "my grandmother or future employer" to see. I didn't have a grandmother I regularly saw, and I was ten years away from getting a real job, but still, I was terrified. In that class, I was scared straight into believing that my future employer would have a log of everything I would ever post on the internet and use that to judge whether I was employable. And that an accidental slip of a finger would prevent me from ever getting a job and lead me to a lifetime of unemployment. And unemployment meant I would have to go live in a forest with no shoes and hunt bunnies to survive. And bunnies were adorable, and I didn't want to eat them, and now I had yet another thing to worry about in my youth.

This digital footprint lesson coincided with the Edward Snowden NSA leaks. I was told to operate from the understanding that everything I said and did would be watched by an NSA agent. Not only was my faceless future employer watching me, but so was the Government.

I was at the age when I should have been worrying about the elf-on-the-shelf and what he would tell Santa Claus, but instead, I was worried about government surveillance. Growing up as a brown person in a conservative town, post-9/11 and Patriot Act, made ten-year-old me a tweaking little bundle of anxiety. Now, not only did I have to fear God listening to all of my thoughts and the risk of eternal damnation, I was also worried about the things I typed and searched and the music I listened to being surveilled, making sure I didn't say or watch the wrong things and inadvertently get put on a watchlist. And I would spend many nights awake and sweating from nightmares of getting sent to Guantanamo Bay2 for listening to "Not Ready to Make Nice" by the Dixie Chicks.

I had to get a background check done for work last month, and while I have never committed a crime or done anything even remotely worse than a speeding ticket, I was an anxious wreck for the seven days it took for me to pass. We are all acutely aware of our digital footprint, but it is so nebulous. Is it a quick Google search? Can they see my Instagram? Can they see my Instagram likes? And if so, what will they do with it? Will they see those trad-wife posts I've liked and assume that I am an aspirational trad-wife? Will that prevent me from getting a job?

While my vivid imagination leads me to operate on the extremes, anxiety, and social isolation continuously are consequences of these vague models of surveillance. I know I am being surveilled, but I don't know how or when. What that does is make me self-surveil to an extreme magnitude. Stop liking strange things on Instagram reels3 only like posts about how much I love delivering shareholder value and studying engineering, only post pictures where I look like a studious, employable individuality, and lock away my agency to express myself freely.

Big Brother is ALWAYS watching

The ethos behind fearing our digital footprint comes from concerned adults who want me to have a job and become a well-adjusted, self-sufficient adult. "Don't post anything you wouldn't want your grandma or your future employer to see" is, at its core, sound advice that any employment-seeking individual should follow.

However, the cost of this surveillance is how much I censor myself when I write. I love writing about politics and history, but because I know my tastes are subject to change and that anything could be found, misrepresented, and misconstrued, I have to find creative ways to say what I mean without actually saying the words.

Beyond myself, I think about how many people are out there, silently saving their insights and interesting thoughts to themselves and not sharing them for people to see and engage with out of this same fear of losing their jobs and livelihoods. This fear is entirely founded—there have been so many instances of people getting fired from their jobs for posting something on the internet, such as a simple comment on a Facebook post.

Instead, they live in silence, too scared to even like a dumb Instagram reel if it pleases them. These fears are rational—surveillance is worsening4, with increasingly drastic consequences. And as a result, we have become our own prison guards, policing our own thoughts and expressions before they ever reach the digital world.

The panopticon doesn't need to watch everyone all the time. We just need to believe it might be watching. And in that belief, we cage ourselves. We prevent ourselves from writing, from creating the content that we want, and most tragically, from getting elbow-deep into the wretched corners of the internet and finding the absurd videos that make us giggle; we lose the digital dead birds we want to drop at our friends' feet as tokens of love and affection.

Thank you so much for reading! This was so fun to write, please be responsible about your digital footprint!

essay about dangers of early 2010 tumblr.com is in the works.

DO NOT GIVE YOUR CHILDREN UNLIMITED ACCESS TO THE INTERNET

no I won’t

I’m so glad I have the privilege of being a recipient of the absurdity

Okay feature!