Paranoid And The End of Times

on the cultural importance of black sabbath and metal

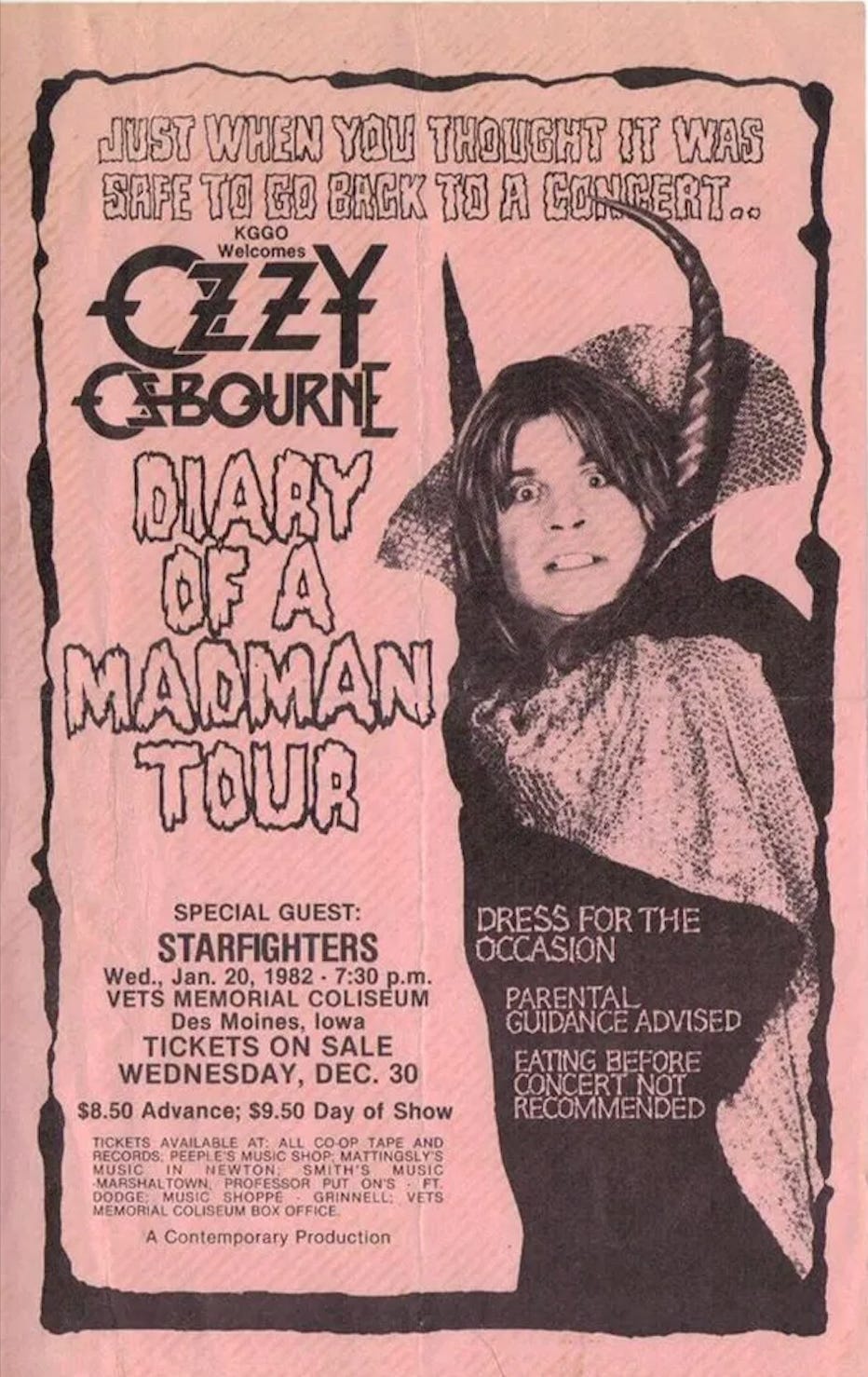

I originally wanted this essay to be an analysis or review of Paranoid by Black Sabbath, a part of a project where I write about my twenty-one favorite albums of all time. While I was writing, I realized I have nothing unique and interesting to say about one of the most critically acclaimed albums of all time.

So instead, I am going back to my roots and talk about history. So enjoy the next thousand or so words, where I make a genre of music commonly associated with brain-dead head banging really nerdy!

One of the most terrifying things a girl can do is share her opinions on heavy metal on the internet. If I had a nickel for every time I told a man I liked metal and he asked me to name five songs by a metal band, I’d be a very wealthy woman. And if I had another nickel for every time I did name five songs, only for him to say Black Sabbath didn’t count or that thrash metal wasn’t "real" metal, I’d be even richer.¹

But alas, I am a brave woman. And I love this album. So I’m writing about it.

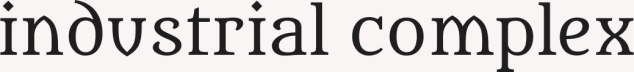

On January 20, 1982, Ozzy Osbourne—former frontman of Black Sabbath—bit the head off a live bat at Veterans Memorial Auditorium in Des Moines, Iowa, during his Diary of a Madman Tour. He had already been kicked out of Sabbath by then (even by rock and roll standards, Ozzy's drug use was too much) and was replaced by Ronnie James Dio. (the guy who invented the rock and roll devil horns sign). A fan threw a bat onstage, and Ozzy, thinking it was fake, bit its head off. That’s metal, baby.²

Thirty-two years later, another legend would take that same stage for a rousing performance of Santa Baby—that legend was me at my annual Christmas Dance recital.

So when I got older and heard the story, I clung to it, rock and roll history tied to a place I once danced in a frilly little tutu— a rare piece of relevance for a culturally starved Iowan like myself. The Ozzy-Bat incident eventually turned me, a little ballerina girl, into a metal fan.

But Ozzy and the Bat wasn't my first introduction to metal. I grew up just outside Des Moines, the birthplace of prolific metal band, Slipknot. Despite being my city's sole claim to musical fame, Slipknot wasn't exactly beloved in my conservative, Christian town. Their entire aesthetic, screaming in masks and prison jumpsuits, was the antithesis of the Jesus-loving, country-music-blasting" good old boy" rhetoric.

I wasn't raised Christian, but I absorbed enough secondhand religious dogma from the local holy rollers that I was still extremely worried about the state of my soul, purgatory, and the ever-present threat of eternal damnation as a child. I was terrified of burning in hell for all eternity alongside the deplorable freaks in screaming masks. As a result of my overactive imagination and community that believed the Hot Topic store in mall was alternate portal to hell, I had many nightmares about Slipknot as a child, leading me to avoid metal as a genre for most of my life.

I gave metal another chance when I was about sixteen after I learned about Ozzy and the bat. I felt drawn to it this time, not despite its reputation but because of it. In typical edgy teenager fashion, I was obsessed with the kind of music that pissed people off and made conservative PTA moms clutch their pearls. The same people who were fundamentally at odds with everything I was and everything I believed in.

At that age, I wore severe black eyeliner and dyed my hair purple, and my nightmares were no longer filled with images of hellfire but the world around me. I was politically involved, increasingly angry, and constantly butting heads with the “good old boys,” who hung confederate symbols from the back of their pick-up trucks (you have to be a special type of racist to rep confederate flags in the midwest). And I couldn't stomach listening to another jingoistic, feel-good Toby Keith song I grew up hearing on the country radio.

The first metal album I ever listened to all the way through was Paranoid. I'm not a musician and don't have any fancy technical analysis. All I can say is: that the album just sounds sick.

But sounding cool is only half the battle for making a generational record. Any iconic rock band needs mythology, mystery, drama, and controversy to stay relevant within the cultural zeitgeist. Whether it's in-fighting, outrageous personalities, moral panics, or rumors about Satanism and witchcraft—Black Sabbath had it all. The controversies and their unique sound made Paranoid one of the most influential albums of all time.

The Historical Context of Paranoid

Paranoid emerged during a particular historical moment. After World War II, a brief period of cultural euphoria gave rise to the hippie movement of the ’50s and ’60s, a prominent youth counterculture defined by peace, love, and idealism. This era of economic prosperity gave us free love, beat poetry, and a lot of good, happy music. The Beach Boys were singing about “Good Vibrations,” the Beatles were deep into their Sgt. Pepper era, full of technicolor optimism and psychedelic joy. Pop culture at the time reflected a widespread, almost utopian belief in a better future.

But toward the end of the ’60s, the world became too dark for peace and love. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Vietnam War draft, and the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation made this youthful optimism a naive daydream. And for the young people who had grown up during the post-WWII economic prosperity, this darkness was disillusioning.

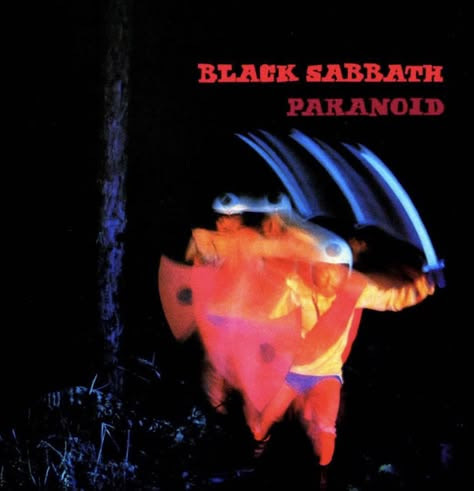

Enter Black Sabbath, from Birmingham, England — a post–World War II industrial city downtrodden by the aftermath of the war. All four original members — frontman Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, and drummer Bill Ward — came from working-class backgrounds.³ They spent their days doing factory work and playing music after long shifts on the line. Famously, Tony Iommi lost the tips of his fingers in an industrial accident right before Sabbath formed. To keep playing guitar, he crafted homemade thimbles and detuned his strings to ease the pain, creating the band’s dark, sludgy sound.

This working-class doom and gloom is an essential context for understanding Paranoid. The album is full of political commentary, but it doesn’t try to convince the listener of anything; instead, it provides a glimpse into the world as they see it. The lyrics in Paranoid reflect what the band lived through: war, fear, addiction, and a general sentiment that the world was falling apart.

The Album

The opening track, “War Pigs,” is a scathing critique of the Vietnam War, which is especially interesting, considering Black Sabbath were a British band and at the time, many American bands were avoiding overt political commentary.

Politicians hide themselves away

they only started the war

Why should they go out to fight?

They leave that role to the poor

The song is also laced with religious imagery, references to witches, judgment day, and Satan himself. Between their name (Black Sabbath) and their constant callbacks to Christian iconography, it’s not hard to see why the band was repeatedly linked to Satanism and the occult. But when you actually look at the lyrics, the message reads very Christian.

Now in darkness, world stops turning

as she is aware there's bodies burning.

No more war pigs of the power

Hand of god has struck the hour

Day of judgement, god is calling

on their knees, the war pigs crawling

Begging mercy for their sins

Satan, laughing, spreads his wings

Bassist and primary lyricist Geezer Butler, who grew up Catholic, argues that “war was the big Satan.”⁴ The song is a fundamental embodiment of the Catholic fantasy, sinners facing their fate on judgment day.

Hand of Doom: This song addresses the aftermath of war. Ozzy sings about drug addiction and despair, criticizing how society abandoned veterans. The “hand of doom” represents heroin’s deadly grip on a generation of lost soldiers.

Electric Funeral: This track imagines a world depict radioactive fallout and the end of humanity, an obvious response to Cold War-era nuclear fears. Black Sabbath confronts the listener with the specter of nuclear holocaust.

Scary Music

Ozzy Osbourne once explained the band’s origin story, “It was the end of the 60s, it was all ‘If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear a flower in your hair.’ What a load of old fucking happy hippie crap that is. Here’s us living 99 million miles away in Aston, Birmingham, an industrial city, and the world wasn’t happy. We used to rehearse across the road from a movie theatre, and [Sabbath guitarist] Tony Iommi said to us, ‘Isn’t it weird how people like to go to the movies and get scared? Why don’t we start making music that scares people?’ And he came up with the heaviest fucking riffs of all time.⁵”

“Isn’t it weird how people like to go to the movies and get scared? Why don’t we start making music that scares people?”

Paranoid is a scary album. Scary like the the horrors of war and abandoned industrial society. Realities that are much more terrifying than the purgatory that supposedly awaits us all if we accidentally have a lustful thought. And the aesthetic matched. From the dark album art to the spooky, theatrical live performances, Sabbath leaned into this frightening imagery. They wore black clothes, used haunting visuals, incorporated upside-down crosses, and even released albums on Friday the 13th—all part of building rock and roll folklore needed to sell records.

But with that darkness, much of it for marketing sake, came misunderstanding. From the very beginning, Black Sabbath (and metal as a whole) was caught up in moral panics, often accused of promoting Satanism, violence, and corruption of the youth; very ironic considering that Sabbath was trying to make music about those evils, not glorify them.

My favorite example of this is the song, “After Forever” from Black Sabbath’s heaviest album, Master of Reality.

Could it be you're afraid of what your friends might say

If they knew you believe in God above?

They should realize before they criticize

That God is the only way to love

This outwardly evangelistic sentiment :"God is the only way to love," was one I have heard many, many times growing up, from Bible-thumping evangelical salesmen knocking on my door to my well-meaning friends, who were genuinely concerned about the state of my soul.

But the “moral” authorities saw the inverted crosses and black clothes, ignored the lyrics, and labeled metal the enemy. And it's easy to do that, to assign an entire genre of music as the scapegoat for delinquency and moral decay, instead of confronting the systemic problems that might be making young people feel alienated in the first place.

And yet, despite (or perhaps because of) that, Paranoid influenced generations. Sabbath didn't invent metal (you could give some of that credit to Deep Purple or even Led Zeppelin), but Sabbath was the first to embrace the genre in its entirety: sound, image, and associated controversy.

Heavy Metal and Reagan’s America

Following the influence of Paranoid and Black Sabbath, metal became extremely popular in the US in the 1980s. This was during the Reagan era: War on Drugs, the AIDS crisis, Cold War tensions, and a national obsession with returning to a better time with “traditional American values” (sound familiar?). Culturally, the US was experiencing a resurgence of conservative values reflected in mainstream social sentiment.

At the same time, bands like Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, Slayer, and Mötley Crüe were dominating the charts and racking up award nominations. And all of them pointed to Black Sabbath as a crucial influence on their sound. The ’80s gave rise to a whole spectrum of metal subgenres: thrash metal, hair metal, glam metal. Despite their differences, they all shared some key traits: fast playing, pounding drums, screaming frontmen, and a loud, angry energy. The fashion followed suit — long hair, leather, gaudy makeup. It was gauche and campy response to conservative cultural repression.

When your parents want you to be a good little God-fearing Bible boy in a button-up, collared shirt, but you don’t see yourself in that perfectly manicured, conservative wet dream— you revolt. You put on eyeliner and tight leather pants, pick up a guitar, and dive headfirst into a Lovecraftian fantasy, screaming about this sick and twisted evil world. In fact, there’s a reason why many prominent metal bands (especially those known for particularly heavy music) came from deeply culturally conservative places — Pantera from Arlington, Texas; Lamb of God from Richmond, Virginia; and Slipknot from my very own Des Moines, Iowa. Metal has always been a reaction to cultural repression, a middle-finger in the face societal expectations for conformity.

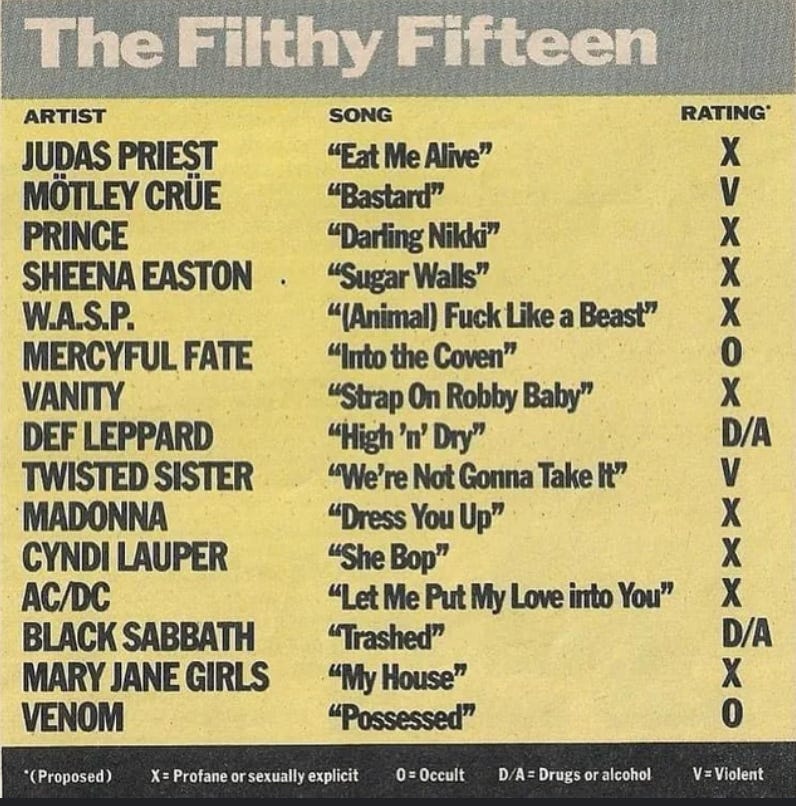

In 1985, the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), led by a bipartisan group of senators' wives, launched a crusade against music they saw as threat to societal welfare. They published the infamous “Filthy Fifteen,” a list of songs flagged for violent, sexual, or occult content. Nine of them were metal.⁶

Famously, Dee Snider of Twisted Sister had to testify in front of the Senate during the PMRC hearings in 1985. In a later op-ed reflecting on the experience, he wrote:

“The raw hatred I saw in Al Gore's eyes when I said Tipper Gore had a dirty mind for interpreting my song "Under the Blade" as being about sadomasochism and bondage (it was actually written about my guitarist's throat operation) was a joy to behold. They really should have vetted me better before allowing me in to speak.”

- Dee Snider, in an oped about the trial.⁷

To this “moral majority,” metal was a threat to society—a corrupting force warping the minds of innocent, impressionable youth. After the hearing, record labels responded with Parental Advisory stickers on albums, but it only added to the allure. Like a teenager sneaking their first sip of alcohol or slipping out the bedroom window past curfew, listening to this “forbidden music” made them feel grown-up, rebellious, providing them with superficial agency in a ultra-repressed world.

Perpetually Paranoid

After its peak in the 1980s, metal’s mainstream popularity waned. In the ’90s, grunge took over, with bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and Alice in Chains who all citing Black Sabbath as a foundational influence. The sound shifted, but the themes stayed familiar: disillusionment, alienation, anger. Meanwhile, metal itself was evolving, with the emergence of bands like Korn, Limp Bizkit, and Slipknot who brought a more chaotic, genre-bending sound.

Paranoid’s importance extends far beyond the album or its specific moment in history. The themes that Paranoid tackled are just as relevant now as they were in 1970’s: war, addiction, political turmoil, the looming threat of nuclear disaster. Like any kind of art, musicians aren’t politicians or authorities we should look to for solutions to these existential threats (Ozzy Osbourne bit the head off a live bat, for God’s sake!) But the music matters because it is a reflection of the fundamental horror of living in a unpredictable, repressive society.

Metal not a comforting stroke on the cheek telling you “everything will be okay.” It’s affirming in a different way — maybe everything is as bad as it feels, and the only thing that can temporarily drown it out is a guy with long hair and too-tight leather pants screaming about it over a sick guitar riff.

As I’ve gotten older, my relationship with my hometown band has changed, too. I’ll be the first to admit: Slipknot is still too heavy for me (poser alert!). I don’t particularly like most of their songs — but I understand them now. The band that once haunted my childhood nightmares doesn’t scare me anymore. What scares me now isn’t Slipknot — it’s the world they were reacting to. Both Slipknot and I are from the same place: the “barren wasteland,” as frontman Corey Taylor⁸ once called Des Moines. It’s a place no one really cares about, where literal tumbleweeds roll through the so-called “downtown” and conservative religious zealots meet the abandoned ruins of rural America. If you’re from there, you know that Ozzy Osbourne biting the head off a bat onstage is honestly a completely rational response to being in Iowa.

And that’s exactly why music like this matters. This is why studying the cultural impact of popular music is important. Pop culture is culture, and culture is history. It gives us insight into the past, but it also offers a glimpse of where we’re going. Especially now, in a world full of contradictions and complexity, pop culture reveals just as much, if not more, about the economy and political state of the world, than the Consumer Price Index or the Dow Jones ever could. ( Brat, Lady Gaga, and the resurgence of house music told me that the stock market was going to crash today, actually.) What metal shows us, from Paranoid to Slipknot, is that repression breeds rage, and that rage needs somewhere to go.

Paranoid is more than just an incredible album; it captivated generations of young people and inspired them to turn their dread into something, a response to the world, to make scary music for scary times.

You can support my writing by engaging with my work, sharing your thoughts, and reaching out. I also recently started a new project where I force my friends to write weekly media reviews. Check it out here!

I used to run a twitter account for music criticism when I was a teen. Very traumatizing.

https://americansongwriter.com/meaning-behind-black-sabbaths-menacing-hit-war-pigs/

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/oct/31/horror-films-and-heavy-metal

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/1985-pmrc-senate-hearings-then-and-now_b_8136698?1442323560=

I accidentally deleted this essay while I was reorganizing my writing, so enjoy!

Totally awesome read!!!!! Love it. I’m a huge Slip Knot fan BTW. I credit them with bringing me back to metal fandom - I’d ventured off for a good many years. I’m similar vintage as those guys and share a similar record collection that floored me that wasn’t metal like Jane’s Addiction Nothing Shocking mixed in with our Maiden and Ozzy ans Slayer . What they’ve done for music generally in the last (gasp almost 30 years), impressive. I love the history you bring here. I would love to see more women talk about their experiences with the music and their POV on the lyrics. For a lot of us GenX types, Ozzy was our gateway to Sabbath because we were just a little too young to have a had chance to experience them in tact.

Thanks for writing!!!

Outstanding thinking and writing going on here Aishu. Keep moving forward!